Commissioning of the Laminas 2700 dish - the first day

Preparations for the commissioning of the Laminas 2700 dish began on Friday, July 31, 2020. The sky was completely cloudless and the sun was burning all day, so the temperatures climbed to 30 ° C. That's why I started work until the evening at 18:00 Central European Summer Time.

The initial state was a dish attached to the EGIS positioner. I had a program on my laptop that allowed me to move the dish in the azimuth and elevation directions. I used VU + Duo2 as a receiver. I am quite far from the satellite receiver in the living room to the place of the dish, so for the first attempts I used a 45m coaxial cable Belden H125 CU, which will be needed for the final installation.

The task was to capture the signal from any satellite. I was the first to choose the 28.2 ° E position. There is a satellite with a strong signal in the European beam suitable for finding the correct direction of the dish. Subsequently, there are satellites in the British beam with a sufficient range of weak signals to test the capabilities of the dish.

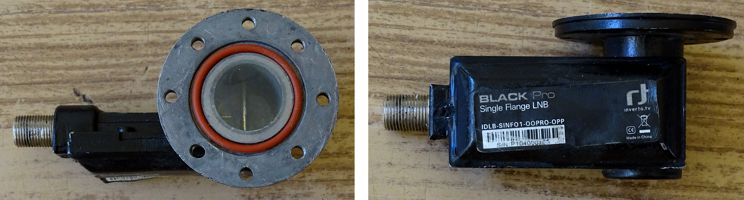

Not knowing what a strong European beam signal from such a large dish would do to a conventional converter, a friend brought three different LNBs for comparison.

Fig. 1 - LNB Inverto Black Pro

We were the first to use the MTI AP8-TW LNB. My idea of a comfortable assembly from the ground soon took over. Even with the parabola tilted to the maximum, it was necessary to work from the upper rungs of the ladder.

I had no idea how long it would take to pick up the first signal. Nowhere on the web have I come across a procedure on how to aim a large dish with a narrow beam angle for the first time, or how long it can take. But the beam angle of my dish of 0.75 ° suggested that it would be a search for a needle in a haystack. The first idea that we would just cross the whole sky with a parabola was obviously unrealistic nonsense.

For the first rough orientation, I decided to use the EGIS pulse counter. First, I used a compass to point the back wall of the EGIS positioner north, as indicated by the arrow on it. Then I turned the tube of the support mast by an offset value of 25.5 ° to the west. This made approximately 30 mm on the circumference of the 133 mm diameter support tube. In this position, the zero point of the EGIS positioner should be in the direction of 90 ° of the magnetic azimuth. From the knowledge of the number of 200 pulses per degree, I calculated that for the satellite position 28.2 ° E, ie the magnetic azimuth 160.1 °, the EGIS must be set to the value of 14020 pulses. For elevation, I calculated in the same way that the EGIS must be set to 17600 pulses. Of course, provided that the mast support tube is ideally positioned vertically.

We placed an orientation inclinometer on the supporting frame of the dish. According to his data, the correct elevation should have been 2 ° larger than the set position from the calculated EGIS pulses. But we didn't really believe in the accuracy of this device.

Behind the dish, we created an improvised control center. It consisted of two tables. The first was a satellite receiver with a monitor and liquid snacks. There was a laptop on the other table to control the recording device.

As expected, after starting all the equipment and setting the expected position on the positioner, the signal from the satellite was zero. So I began to move the plate carefully in the azimuth direction in both directions. We didn't pick up any signal. We took the advice of the inclinometer, added a little to the elevation, and again drove the azimuth around the expected position. Signal still zero. We repeated this procedure several times and still nothing.

Fig. 6 - Orientation inclinometer

At this point, doubts were beginning to come as to whether turning the offset dish horizontally was nonsense. When I was thinking about which direction to expand the search, I came to the conclusion that I would have a bigger mistake in the azimuth direction. On the one hand, I didn't really believe in the accuracy of the compass, in addition to the error of the compass, a possible error of turning the support tube by an offset angle is added. Looking at the dish, I felt that it was facing far east. I trusted the calculated elevation much more.

For the next hour, therefore, I moved the parabola in the direction of azimuth with increasing scattering. And then suddenly a signal with a strength of about 0.7 dB appeared. My colleague and I cheered, drank to victory and began to specify the elevation. Unfortunately, no matter how hard I tried, I didn't get over 1.4 dB. With such a signal, the receiver did not tune anything, so we had no idea if it was a signal from a completely different satellite. So we decided to try another LNB. After disconnecting the coaxial cable from the LNB, the signal jumped to 6.7 dB. From this it was clear that we were not picking up a useful signal, but only some local interference. After connecting the Invacom SNF-031 LNB, the signal was zero again.

This LNB seemed to be a little more resistant to interference by a strong foreign signal. So we repeated the movement of the parabola along the selected section of the sky with this converter. Still zero signal. At this point, we have already voiced the idea that a horizontal offset dish is nonsense. Disappointed, I wondered if it made sense to continue. Since it was already 22 o'clock and all the refreshments were drunk, we decided after three hours of futile efforts to end the attempts for the day.

But I could not accept such a failure. I began to think that I should try to find another satellite with a strong signal. Therefore, I returned to the garden, calculated the theoretical position of the Astra 19.2 ° E, and started hunting again. And in vain again. At that time, I was no longer thinking about whether the tested directions of the dish were real or not. I jumped the elevation and passed the azimuth in the range of more than 90 °. And around 11:30 PM, I finally came across a 10.5 dB signal. It was really an Astra 19.2 ° E. The first program I saw on the monitor was German DMAX.